Welp, it’s New Year’s Day, so time for that annual introspection that seems to be catching in this modern era. My New Year’s Eve saw me in bed by 9:30 pm, in part because I was running on 4 hours of sleep having spent, after a full day of work with my now-customary long commute, two hours wrapping presents and 3 hours driving to my destination the night before to have a belated Christmas celebration with family, as an abundance of caution after a COVID exposure (but not infection, thank goodness) delayed us by a week.

Unwrapping presents while everyone else was making cocktail party plans was a bit disconcerting, but didn’t put a damper on the joy of watching my young nieces unwrap their presents, and then the eldest had to help everyone else unwrap theirs.

But the whole delay has made me think about the concept of time, and how people celebrated historically. NPR published an article a few weeks ago about the illusion of time, and our modern obsession with it. Thanks to internet-connected digital clocks - mainly through our phones and computers, we’re all more aware of time than ever. We obsess over whether we’re a minute or two late. Some folks have time clocks that pay them down to the minute, or jobs that track their movements and productivity down to the second. It can be easy to associate this obsession with time with our modern Information Age, and you’d be right. But while our modern atomic clocks are marvels of technology, our entire system of time, dates, months, etc. is intimately connected to the cyclical nature of our natural world.

We mark the earth’s revolution around the sun and call it a year. A month originally derived from the 28-day lunar cycle - until the Romans decided to mess with it. The earth’s rotation is a day. We’ve divided the day into 24 hours, each hour into 60 minutes, each minute into 60 seconds, etc. We can thank the Babylonians (and possibly also the number of joints in our fingers) for dividing things into 60s.

Historically people, like animals, spent the vast majority of their time in food acquisition. Hunting and gathering, food preservation, agriculture, etc. was not only humanities primary focus until more recently than you’d think, but also was intensely guided by the seasons. Humans ate what was in season when, followed herds, fish, and game on their own food-related migrations, and far from the equator, hunkered down for long winters.

In Medieval Europe, the origin of many of our modern holidays, Christmas was the feast that followed the month-long Advent fasting, and not a particularly big deal in the liturgical calendar. Christmas itself did last twelve days, until Epiphany, coming up on January 6. The Swedes (and my Swedish immigrant community growing up) celebrated Tjuegondedag Knut (or Tjugondag Knut), which was typically celebrated on January 13th and marked the end of the Christmas holiday, when you ate up all the leftovers and danced around the Christmas tree one last time before throwing it out in the snow.

In our modern era, the holiday season often lasts from Thanksgiving through to Christmas itself - a bit topsy turvy from the Medieval fasting season of our ancestors. Christmas itself is a Christianization of the winter solstice, which typically falls somewhere between December 20 and 22.

Historically, people kept track of time for a whole host of reasons, but keeping track of major events was a big part of it. Even before we invented time as we know it today, tracking historical events was hugely important, from Aboriginal Australian’s incredibly accurate oral history traditions to the equally important and accurate Lakota Winter Counts.

We can thank railroads for giving us time standardization and time zones - previously people hand-wound mechanical clocks by sunrise and sunset, which varied greatly from place to place. And we can thank industrialization for giving us time clocks, 12-14-hour workdays, and, ultimately, the weekend. It took fighting to the death to give us “8 hours for work, 8 hours for rest, 8 hours for what we will.” But even so, 8 hours of work a day is considered by many to be a logical fallacy. In most households, there is never 8 hours for what you will - most of those 8 hours are taken up by commutes, grocery shopping, food preparation, bathing, cleaning and maintaining your home. To such an extent that few of us get 8 hours of sleep a night, despite scientific evidence that ample, high-quality sleep is essential for health (all that blue light isn’t helping, either).

There’s also the whole issue in our modern society of overwork, the companion to under-rest. Although Medieval peasants had much harder lives than us, they did actually get more official holidays and time off than modern Americans (although that time off didn’t generally include individual food production and preservation). Sadly, John Maynard Keynes’ prediction that in the future families would work as little as 15 hours a week, we’ve still got until 2030 to make his hundred years’ prediction come true. We’ve certainly done it before. Evidence suggests that hunter-gatherer societies worked about 15 hours a week. Maybe we’ll get there again. Millennials (ahem) and Gen Z certainly want us all to have better work-life balance.

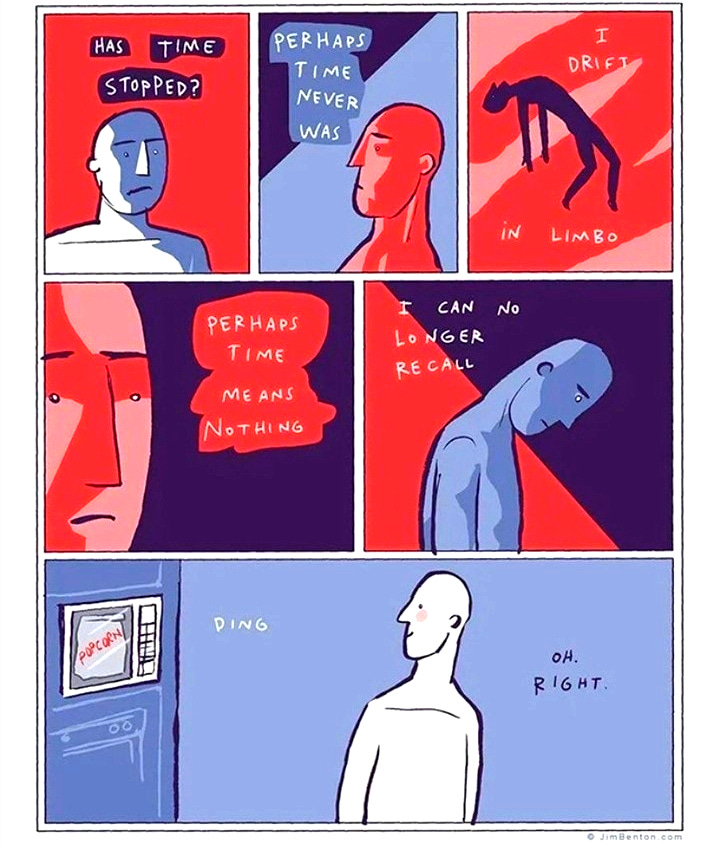

The pandemic, also, disrupted our concepts of time. COVID seems like one of those world-shifting events, like 9/11, that sort themselves in your brain into “before” and “after.” So much so that while 1980 still feels like 20 years ago for those of us who tracked time by the millennium, life before the pandemic simultaneously feels like last year and 10 years ago.

2022 felt like that for me. It was a year of incredible change, some bad (my mom dying), some good (a new job with benefits and a living wage). But so much happened, it feels like it was 5 years ago, instead of a single year. At the same time, the year feels like it has flown by.

Grief has negative impacts on productivity (unsurprisingly), and we all have collective grief not only for all the people who have died from COVID or otherwise, but also we grieve for what was, and what could have been. COVID was incredibly disruptive to our daily lives, derailing future plans, family time, and our sense of safety. If sleep quality is more important than quantity, in a way, so is time.

One thing I’m grateful for about 2022, despite all the bad things that happened, is that I got to spend more time with family. But it shouldn’t take a death to bring us together, so one of my unofficial resolutions is to spend more time with the people I love.

That being said, my Word of the Year is “balance” (last year’s was “cultivate”). 2022 made balance tough. My new job, as much as I love it (and the benefits and living wage), comes with a 40 hour workweek and a 70-90 minute commute - each way. I tried to keep up with the same pace of Food Historian work I maintained back when I was working 30 hours a week with a shorter commute, and it’s not been great for my health. I did seven Food Historian talks in December alone, on top of parties, baking, shopping, wrapping, card-writing, etc. It was too much, which is why I’ve been fairly radio silent of late.

So, in order to keep the balance, I’ve resolved to give a little. I won’t be accepting as many talk requests or media requests. I won’t be responding to research requests from individuals. I just can’t keep up.

I won’t, however, give up my writing. I love writing, and I’m always proud of the work I manage to squeeze out in my in-between hours. I’m going to try to prioritize some of my precious weekend time for at least once-a-month posts here on Substack, my blog, and Patreon. But I also want to get serious about devoting more time to my book. One of the benefits of my new job, despite the longer hours, is that it is much lower stress than my old job, so that I find I have more intellectual bandwidth for creativity in my time off.

As a treat to myself, I’m also burning a precious personal day and taking Tuesday off, in addition to the Monday holiday I get. A four day weekend for the first time since August, when I drove home to North Dakota for a family reunion. I’m very much looking forward to it, even though I’ll have to use some of that time off to clean our neglected house. Not having to get up at 5:30 or 6 am to drive to work will be an added bonus.

We all have a limited amount of time on this earth. I’m bound and determined to make mine as quality as I can, since no one knows the quantity we’ll get.

If you make any New Year’s resolutions in our arbitrary celebration of one complete revolution of the Earth around the Sun, I hope you’ll join me in making a commitment to balance and quality time. Here’s to another year on the planet. Be good.

How fascinating! I also went down the Time 🐇🕳️ and shared a Substack post about it:

https://kenshostudio.substack.com/p/measuring-the-infinite

This is beautifully written, both personal and universal. Thank you, Sarah. And I love ‘balance’ for 2023.