This is part two of my series on the Future of Food. Last time we tackled agriculture. Let’s be honest, that was intense. This time we’re going to tackle an oft-overlooked aspect of the future of food - transportation.

We generally don’t think about where our food comes from when we visit the grocery store. Most (but not all) foods in the United States are labelled with their country of origin. But aside from that, it can be difficult to know where our food comes from and how far it traveled.

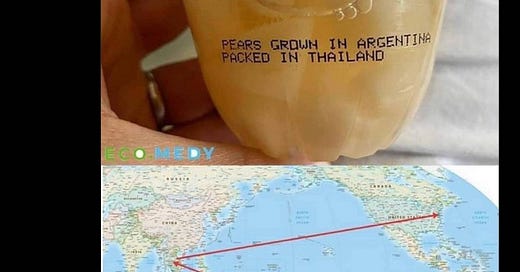

This meme I saw going around Facebook a few weeks ago is a great illustration. It reads: “capitalism is efficient” and then shows the printed text on a small plastic cup of fruit. The text reads, “Pears grown in Argentina, packed in Thailand.” The meme then shows a map illustrating the incredible distance from Argentina, to Thailand, and then to the United States. Fresh pears were flown from Argentina basically the longest way across the Pacific to Thailand, processed and packed, and then shipped (likely by boat) to the United States, and then trucked across the country from California to New York, where presumably the person purchased the pears. That might be cost-effective in terms of dollars, but it certainly is not efficient in terms of energy.

Carbon-Neutral Shipping

In my day job I work at a museum, and we just put together an amazing exhibit on sail freight. Funnily enough, it’s where my two loves (food history and the Hudson River) collided unexpectedly. Proponents of sail freight argue that sailing vessels can be used to move goods around the globe in an economically competitive way and help reduce and eliminate the use of fossil fuels. Sail freight is still in use in small island nations around the world, and was used in the Western world until after WWII, when marine diesel and containerized shipping began to take over. But profligate use of fossil fuels are what got us into this mess. Today, 30-40% of all shipping is just moving fossil fuels around, which is a shocking number. If we were able to eliminate even a portion of our reliance on fossil fuels, we could cut down that number significantly. We had 5,000 years of global trade networks before we figured out steam engines and later the internal combustion engine. Can we get there again?

Although sail freight will be limited to coastal areas and largely to non-perishable or shelf-stable products, even a small reduction in the use of trucks could not only dramatically reduce our carbon footprint, but also ground-level air and water pollution.

Re-localize food systems

There’s a lot to be said for economies of scale, and raising crops where they are most suited to be raised. But our modern food system (starting in the 1870s) has been built almost exclusively on fossil fuels. Between mechanized agriculture, food transportation, and processing, fossil fuels have been at the heart of every step. Importing asparagus from Peru and tomatoes from Mexico in February may be a great way for New Yorkers to have access to those foods in the winter - but flying them in is a huge waste of resources. But then again, so is a hundred farmers driving their refrigerated trucks to NYC’s Green Market. What’s the solution?

During the First World War, proponents of victory gardens argued that they not only increased the food supply, but also reduced the strain on transportation resources. Food raised in the backyard used no transportation resources to get to your plate. Urban agriculture can help offset the needs of cities, and carbon-neutral transportation (sail, solar, electric, and human-powered vehicles) can certainly help. But our local food system of the future isn’t going to be farmer’s markets (which can be very inefficient) and backyard gardening (which isn’t scalable in densely populated urban areas). Medium-sized local farms located close to urban areas seem to be the most efficient in terms of production, shipping, and feeding their neighbors. Of course, that also means that we need to stop building suburbs on top of fertile farmland and stop zoning farms out of existence.

Localizing food systems also includes changing eating habits. Shipping fresh fruits and vegetables halfway around the world so wealthy northern countries can enjoy them “fresh” in the winter months is not sustainable. Food preservation techniques like canning, drying, and freezing can help ensure we more northerly dwellers eat more than potatoes and beans and brassicas all winter long, but eating what’s available in season locally (and dramatically reducing meat consumption) shouldn’t be so hard.

Regional food processing should also make a comeback. Everything from smaller abattoirs to combat our extreme meat monopolies to regional varieties of snack foods like soda and chips. Well into the 20th century regional food processors were king. We can bring them back, support local farms, and reduce how far our food travels, too.

Rethink Packaging

There’s a reason everything we eat these days is packed in plastic - it’s cheap, it’s easy to sterilize, it’s airtight, and it’s lightweight. But plastic is also made of fossil fuels, and despite what lots of children’s programming told you in the 1990s, it’s largely not recyclable. Single-use packaging also accounts for a large portion of food transportation and energy use, as it has to be manufactured, shipped to food processing facilities, and then shipped with the food inside it.

Obviously we can’t get rid of food packaging altogether, but we can dramatically reduce it and choose better materials. Cellophane made a splash in the 1920s, but we largely subsisted on glass, aluminum, paper, cardboard, and the waxed versions of those last two well into the 1960s. Paper and cardboard, even waxed kinds, are pretty biodegradable, and most cardboard is at least partially made from recycled paper. Glass is endlessly recyclable, although energy-intensive. But milk and soda bottles used to be washed and reused, rather than thrown away or recycled. Regional dairies and soda bottling companies would collect empties to be sterilized and refilled. While plastic is lighter than glass, if foodstuffs aren’t traveling as far, or are traveling on water, weight isn’t as much of an issue.

New research into mushroom- and fiber-based packaging also holds hope for a more sustainable future. And some states like New York have taken steps to ban single use plastic, including plastic grocery bags and polystyrene (aka styrofoam). But single-use plastic is still rampant, especially in food preparation. There’s no need to plastic-wrap fruits and vegetables if they’re not being shipped thousands of miles and handled dozens of times before they arrive on grocery shelves. Some places are also implementing zero waste grocery stores that emphasize customers bringing in their own reusable containers to purchase bulk goods, everything from traditional ones like dried beans, nuts, and grains, to laundry detergent and dish soap. Which is how a lot of foods were sold historically - in bulk.

What do you think?

Big cultural changes are always hard, especially when there is money in maintaining the status quo. But nearly every suggestion above is something we’ve already done in the past. Can we do it again?