Hello everyone! Happy September! Here in New York we’re coming out of a long drought, farmers across the country are starting to harvest early crops (local gingergolds, one of my favorite apples, has been back in stores for weeks) and get one last hay harvest in (or as I like to say, mega-wheats harvest, or marshmallows, for the white plastic-wrapped baleage). I’ve had a whirlwind of film and radio interviews, and a whole bunch of virtual talks scheduled for the fall (which you can see on my website, if I ever get them up).

But I’m also weathering big changes here in the Food Historian household. After 10+ years, I have left the maritime museum for a new job with New York State parks (a historic site), one that I am incredibly excited about, but which involves a much longer commute and battling the edges of NYC traffic. And given that I’m recovering from both my first week of commuting and a COVID booster shot that is making me woozy, I’m going to share some work by my now-former colleague Steve Woods. He’s done some fascinating research around the future of sail freight (which we discussed previously), and has some interesting points to share today, which I find increasingly relevant. As municipalities look to widen highways instead of investing in public transportation and zoning laws allow housing developments to be built on top of prime agricultural land, it’s time to ask, what would it take to preserve our local foodsheds? Steve Woods has some answers:

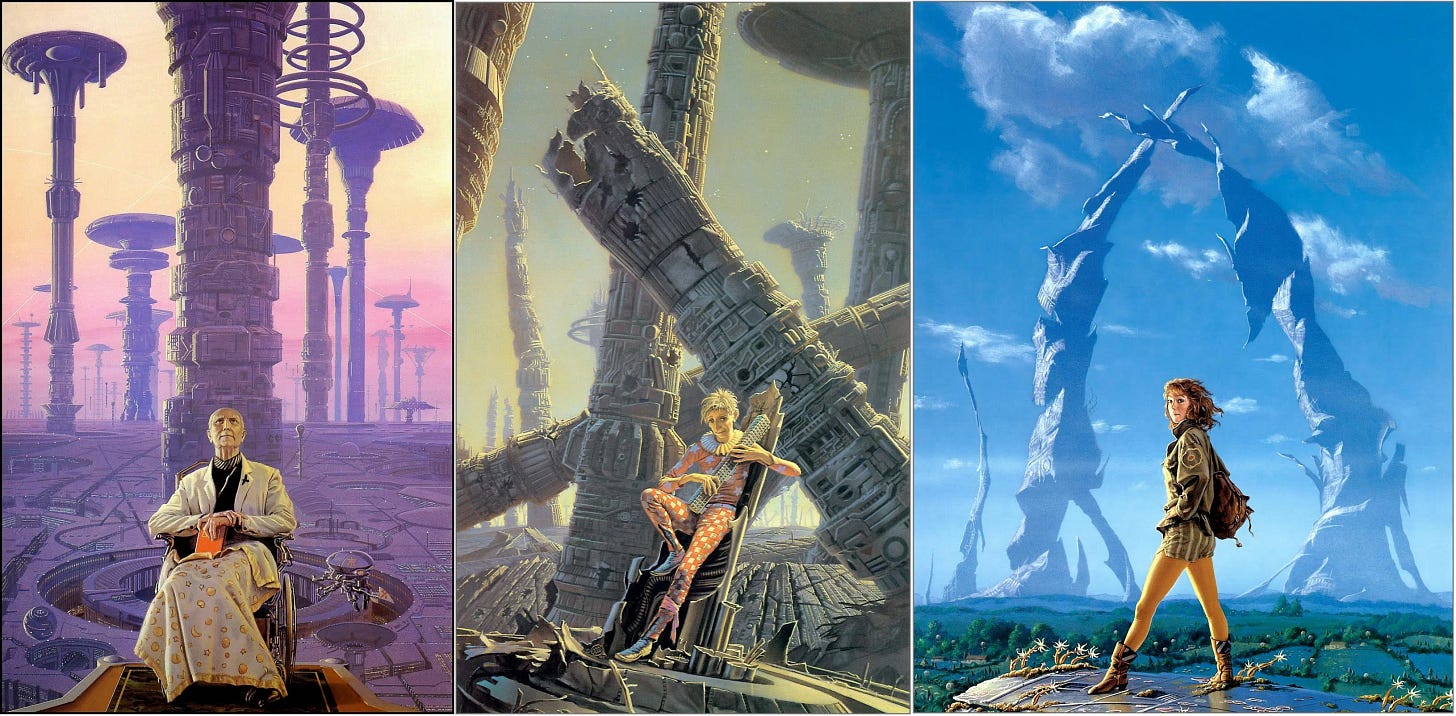

I’ve always been a fan of Science Fiction, and have recently been re-reading Isaac Asimov’s “Foundation” Trilogy. The Trial of Hari Seldon, in Chapter 6 of the first part of “Foundation,” contains an ideal capture of where we are now in the fight for a sustainable future. Seldon predicts the 12,000 year old Galactic Empire will fall within 300 years, and be followed by a dark age of 300 centuries. When asked if this fall can be prevented, he simply states:

[Seldon] A: Yes.

[Inquisitor] Q: Easily?

A: No. With great difficulty.

Q: Why?

A: The psychohistoric trend of a planet-full of people contains a huge inertia. To be changed it must be met with something possessing a similar inertia. Either as many people must be concerned, or if the number of people be relatively small, enormous time for change must be allowed. Do you understand?

Q: I think I do. Trantor need not be destroyed if a great many people decide to act so that it will not.

A: That is right.

(Isaac Asimov, The Foundation Trilogy. New York: DelRay, 2011. Pages 31-38)

As basically the entire membership of the Food Movement Movement, I’ve been researching one of the major challenges of the Great Transition: Getting food from rural areas where it is grown, to urban areas where it is eaten. This gets far harder the longer the Food Supply Chain gets, and the larger the Foodshed. The last time this was studied in depth seems to be 1929, in Walter Hedden’s classic study “How Great Cities Are Fed.”

The future is undoubtedly going to be dominated by rural areas, simply because that’s where all the important things in life come from: Food, Water, Energy, Building Materials, and more. The problem is that there’s only about 50 years of oil remaining, and our transportation systems are entirely dependent on petroleum for their propulsion. There needs to be a plan to make certain the food we need to survive is grown close to our cities and can be transported with carbon neutral means such as Sail Freight. That will be nearly impossible if real estate development and other pressures on local farms are not relieved immediately.

Happily, there is a precedent for how we can deal with this issue immediately, effectively, and justly, above all. New York City conserved a large swath of the Catskill Mountains in the 20th century because it was easier and less expensive than filtering their water supply. The forests and mountains provide a large amount of ecosystem services keeping the water within certain purity standards which would be impossible with large scale real estate development and human habitation in the regions which make up the New York City Watershed.

Taking the same idea, there’s a good precedent for New York City, and every other major city in the US, to do the same with their foodshed. Of course, in New York’s case this would have to reach far beyond the borders of New York State, since the entire agricultural territory of the state can only meet 55% of the City’s needs. As a whole, the Northeast produces very little of its own food, and has been a food importing region for a very long time. The answer is to implement plans like the New England Food Vision, for expanding agricultural land and intensity, by having cities themselves purchase conservation easements on as many farms and undeveloped lands within 500 miles of the City. When rural land comes up for sale, buy and conserve it to be used only as agricultural or forest land, preferably in its current capacity. Forest lands should be designated wilderness if it is contiguous with existing park and forest lands, while farms should be maintained as farms to prevent more carbon-dependent suburban development.

Nothing about this plan will be easy, despite its simplicity. Landed interests and developers will rail against it, as it will limit their options for profit. Politicians will rail against the increase in taxes needed to pay for the measure. Real estate investors will potentially lose out on their profits if eminent domain is used to acquire development rights and preserve farm and forest land from conversion to carbon-intensive, car dependent, suburban cul-de-sacs. The whole idea of land reform in the US seems taboo at the moment, though it is a critical subject to address in both urban and rural contexts. Many farmers will undoubtedly be happy to take the pay for easements if it ensures they can continue to work the land and keep it as farmland, no matter if their next generation continues the trade.

To make this a truly viable plan, there will need to be other changes made to support it. Urban sewage and food waste must be composted or anaerobically digested to make biogas for energy and fertilizer to close the nutrient loop which is so badly broken in our current food system. Other wastes from urban areas must be minimized, and dealt with at the point of production, instead of being inflicted on rural areas in ever-growing landfills. Just prices must be supported for farms the world over, and sustainable forms of transport will have to be rebuilt, such as sailing ships, rail networks, canals, and electrified vehicles. Critically, the power of finance and large scale businesses in the food system will need to be broken or limited through antitrust enforcement and a reform of Federal-level agriculture policy.

Let’s loop back to Hari Seldon and “Foundation.” Seldon’s plan involved centuries of very slow, methodical work to cushion the blow of a process already well past the point of no return, with a very small team relative to the problem at hand. The problem facing us, however, is still on approach to the Rubicon, and can be changed with relatively moderate citizen involvement and cooperation between rural and urban regions in the time remaining. As with most reforms of this nature, we must act decades before we reach the crisis if we are to succeed, and the consequences of failing are possible very dire. Success is eminently achievable, if we put our heads, hands, and hearts behind it, and are prepared to force the issue on political factions: There is no technical barrier involved, only artificial obstacles.

Whether you’re a citizen or a villein, I hope you’ll join me in the Food Movement Movement, and help make the push for a more local and more just food system today.

Steven Woods is involved in creating food transportation and storage systems for a carbon constrained future. He holds two Associates Degrees, a BA in History from LeMoyne College, and a Master’s in Resilient and Sustainable Communities from Prescott College. His Master’s Thesis was on the revival of sail freight in the US as a response to climate change. Steve is from rural New Hampshire, and goes nowhere with more people than trees.

Thanks so much to Steve for contributing today. I hope you follow up on some of his links for further reading. And if you missed the earlier post in the Future of Food series, check out my thoughts on transportation and agriculture:

Do you think Steve’s ideas are possible? Are there farms in your neighborhood? What are they up to this time of year? Share in the comments what you know about your own foodshed, including your backyard, and we’ll see you next time!