Stagflation and Food Prices

World Wars, Trust-Busting, and Corporate Consolidation

Many of us these days may be feeling the rising costs of food, gasoline, electricity, and other essential goods. You’ve probably seen in the news words like inflation, stagflation, shrinkflation. But what do they all mean? And how did Americans deal with inflation historically?

There’s a lot to unpack here, and while I’m not an economic historian, studying the history of food and agriculture means I’ve picked up a few things about depressions and recessions, economics, commodities markets, and government intervention into “free” markets. In the 20th century, at least.

In the last 20 years, income inequality in the United States has grown sharply - Many articles in the last several years have compared the “Roaring Twenties” to the 2020s. But the 1920s were preceded by the 1910s - a turbulent decade at best. While the eventual aftermath of the First World War was a boom, first we had several recessions. 1893-97, 1907, 1910, 1913-14, stagflation in 1916-17, and another recession in 1919-20.

In February of 1917, Jewish women of Lower East Side New York started boycotting food purveyors. In the span of a few months, staple foods like cabbage, onions, and potatoes had skyrocketed by as much as 200%. Fluid milk prices rose sharply, too. People were used to fluctuations in the price of more seasonal items like meat, butter, and eggs. But vegetables? Milk for their children? It was the last straw. Mothers crowded the streets with their children, crying for food and milk. They begged the mayor of New York City for a meeting. Some women took out their frustrations on pushcart retailers, pushing over or destroying pushcarts and produce. Some incidents devolved into riots, with smashed windows and pushcarts. Others roamed neighborhoods, enforcing boycotts of potatoes, onions, and cabbages by destroying groceries, intimidating and sometimes beating those who broke the boycotts. Policemen were bewildered by the actions of the women, reluctant to arrest mothers with children and matronly women. From February to March, boycotts and riots broke out in Boston, Philadelphia, and Chicago.

On February 22, 1917, the New York Times reported, “These food demonstrations are different. Neither the unemployed nor the unemployable are conspicuous among those clamoring for food. They are not asking for work, nor wages, nor charity, but for food. The complaint is not of inability to earn, but of inability to buy what the accustomed wage ordinarily supplies.”

That, my friends, is stagflation. A combination of the words “stagnant” and “inflation,” it’s when prices increase, but wages don’t keep up. For the women of the Lower East Side and elsewhere around the country, their wages had stayed the same, but they could no longer afford enough to eat, much less the little luxuries they used to be able to buy.

Lots of news outlets are discussing stagflation these days, although most are focused on the 1970s, not 1917. But the echoes back then are happening again today.

Back in March, Bloomberg posted a completely out of touch tweet. In it, they suggested that those who “Earn less than $300k” (i.e. most of the United States) could ease the “sting” of inflation by taking the bus, not buying in bulk, trying lentils instead of meat, and closing with “Nobody said this would be fun.” Aside from the lentil thing (I love lentils, and fellow Substacker Cooking with Octopod agreed), which was still a bit out of touch, the advice was terrible. Most of the United States has terrible public transportation, thanks to decades of active disinvestment in favor of individual cars. What little there is is often slow and inefficient, wasting hours a day. Buying in bulk is one of the few ways you can actually save money on food. Telling people not to buy in bulk is pennywise and pound foolish. That last bit was just condescending nonsense.

But clearly well-meaning rich people haven’t learned the lessons of World War I. Then, the suggestion to deal with high food prices was to substitute other, cheaper foods. For instance, rice for potatoes, or fish for meat. But as one Socialist pointed out, increasing demand for cheap foods would only drive up the prices of those foods, too. And the issue at hand was not just food to keep people alive, but the injustice of not being able to afford the same standard of living as just months before. The New York Commissioner of Health purchased tons of smelts to distribute to hungry people throughout the city. Those hungry people protested the move by dumping the barrels of smelts into the sewers - returning them, as one newspaper remarked, to their original habitat (since most of New York City’s sewage went straight into the Hudson).

Although most modern economists are laser focused on whether or not the Federal Reserve should raise interest rates to “cool off” the “hot” economy, some evidence suggest that’s the wrong approach. Because if the economy is cooled off too much, then we go from unaffordable food, housing, and fuel to high unemployment and lowered spending, sending the economy into a tailspin recession. Frankly, in my admittedly limited study of economic history, I think most of the conventional wisdom of economics is bunk. What is the ideal economy? No one knows. All of the advice about the economy is generally in service of the people who control the capital, rather than those whose labor creates it. And our modern economy is 100% focused on endless growth, when we all know we live on a finite planet. What does a sustainable economy look like? Again - no one knows.

Capitalism is only a little over 200 years old (before that we had mercantilism for about a century or two). In that time, our economy has largely swung between boom and bust. If you look at the 19th century, the United States had a major bank panic, and accompanying recession, every 20 or so years, sometimes more often, right up until the present. If you think about the 20th century, we’ve got recessions and depressions in 1907, 1910, 1913-14, 1919-20, 1929-41, 1971-72 (inflation continued as late as 1979), 1981-82, and 2007-09, although the repercussions of that last one are still being felt today. Aside from the post-WWII boom when the United States was rebuilding all of war-torn Europe and defeated Germany and Japan, that’s a recession nearly every 20 years in the 20th century, too.

The Federal Reserve was created in 1913 in reaction to the Panic of 1907, which would have derailed the entire country if not for an infusion of privately held cash by the likes of Rockefeller. We were still on the gold standard at the time, and the founding of the Federal Reserve helped start the movement to get us off the gold standard, which was finally formalized under FDR, who diffused the issue by simply announcing by executive order what the price of gold was. But again, these policies were focused almost entirely on capital and the macroeconomics of labor. For ordinary consumers, the efforts of the Fed were less successful.

There’s one other modern issue that mirrors the Progressive Era, and that’s corporate consolidation, especially when it comes to food.

Today, just ten global food brands control most of our packaged foods. In the United States, just four companies control up to 85% of meat production. The Biden Administration is trying to do something about it. But the consolidation was decades in the making. Our current baby formula shortage is another example. And more researchers are arguing that market consolidation and monopolies are the real drivers behind inflation, including the Fed. American corporations (especially oil companies) are posting record profits, and have been throughout the pandemic and now even as inflation in hitting the pocketbooks of ordinary Americans, corporate bottom lines are largely unchanged, or even better than normal.

During the First World War, state and federal agencies held regular inquiries into price gouging and high prices in general. They used the anti-trust legislation passed under Teddy Roosevelt to go after everyone from meatpackers and grocery retailers to dairy farmers (farmers were later protected from prosecution under anti-trust legislation for cooperatives). Although no real culprit was ever revealed (except for some retail price gouging), that didn’t stop dozens of inquiries that required businesses to turn over account books and submit to public hearings. Even Herbert Hoover, United States Food Administrator, had to undergo questioning from several Congressional investigations.

These days Congressional investigations are focused on January 6, but I, for one, think we could stand to have a few more anti-trust investigations, especially regarding meatpacking.

Obviously, there are other factors at play here. The war in Ukraine, which has made prices for urea and other fertilizers, as well as wheat, skyrocket. Climate change, which is exacerbating droughts, floods, and wildfires that hurt agricultural production of crops and livestock. COVID-19, which shut down or slowed down food processing and harvests (last year farm labor shortages left crops rotting in the fields). Sky-high oil prices, due to ramped down production when everyone stayed home due to COVID and the war in Ukraine.

In World War II, consumers weren’t left to deal with inflation on their own.

The Office of Price Administration was designed to help prevent the inflation that created social unrest during the First World War. Although the United States Food Administration published “fair price” lists in newspapers across the country, they were simply a guide for consumers, and to put some peer pressure on retailers. During the Second World War, the OPA officially set prices for everything from food to clothing to fuel. And had the teeth to go after retailers who didn’t comply. The mandatory rationing system also helped keep prices affordable and ensured limited supplies were fairly distributed.

The OPA was increasingly unpopular with corporations and the business community as the war dragged on, however, and despite its popularity with American housewives, it was abolished in 1947. The United States has seen little effort in price control since then. Richard Nixon issued an executive order in 1971 that froze wages and prices for 90 days. And in the 2000s California and Hawaii attempted to control electricity and gasoline prices, with limited success.

There’s no telling where inflation may go next. Some economists predict it will start to cool off soon, even without intervention from the Fed. But that doesn’t help ordinary Americans still struggling to recover from 2019 layoffs and shutdowns, stagnant wages, and an overall decrease in “real” wages. Food prices are still going up, and although the Biden Administration is trying to help, it might be time for Uncle Joe to bring back some good ol’ price gouging and anti-trust investigations to bring sky-high prices back down to earth. Because inflation is currently at 8.5% - double what it was last year. Even people lucky enough to get raises or cost of living adjustments this year probably only got 2-3%. When raises don’t keep up with inflation, real wages go down, as your dollar doesn’t go as far as it used to.

When that happened just over 100 years ago, we got riots and revolutions. Let’s hope we get some sensible reforms before we get there again.

Further Reading

I’ve written a lot on inflation and price control during both World Wars. Check out some of my previous takes:

For more on the dairy industry, and the connection to those food riots of the Lower East Side in 1917, check out my academic article “Eat More Potatoes: Milk Strikes, Food Boycotts, and the Effects of the High Cost of Living in New York During the Great War, 1916-1919”

If you liked what you read here, you can subscribe, but don’t forget to check out my blog at www.thefoodhistorian.com/blog where most Wednesdays we look at historic propaganda posters from the First and Second World Wars, among other things. Sign up for my email list for blog posts to land in your inbox automatically.

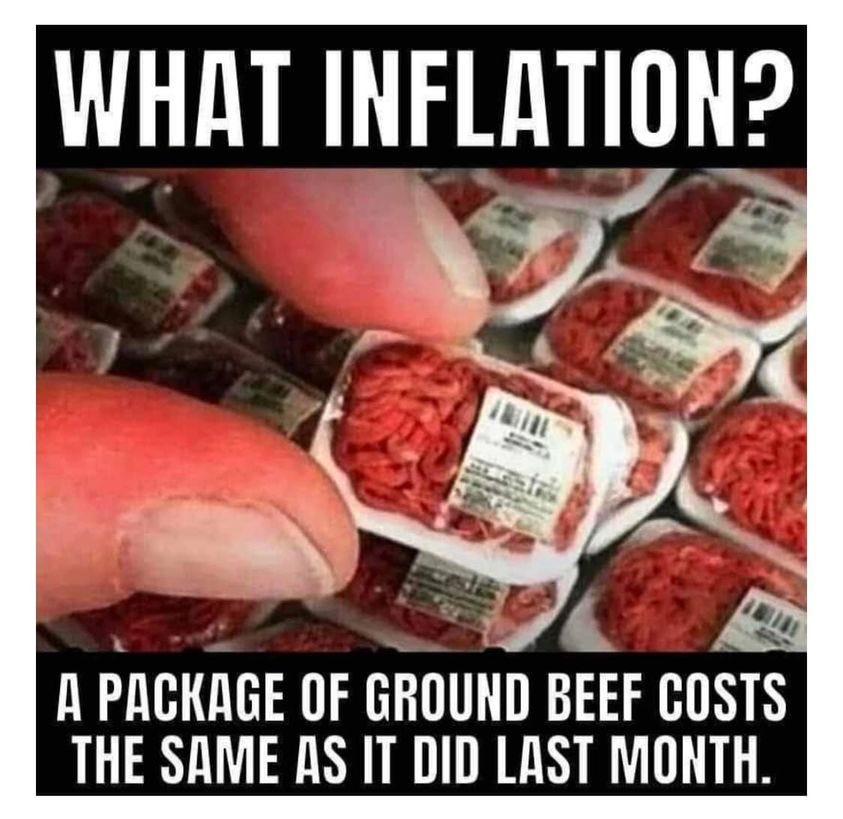

Great article, Sarah. (Love the tiny packaged beef meme)

So much I didn’t know, including the meaning of stagflation. It seems that some things never change--the little guy continues to lose while corporations always come out on top. The chart showing consolidating food companies says it all. Thanks for an excellent piece on a complex subject.