As Heather Cox Richardson said on Friday, this last week was freaking exhausting. These last weeks have been exhausting for me, personally, too, which is why I’ve been a bit radio silent (besides my Scandinavian Midsummer Porch Party series on my blog). But tomorrow is the Fourth of July, which is shorthand for Independence Day here in the U.S. And I’ve been having Some Thoughts about this, so allow me to ramble a little.

NPR shared yesterday a post from 2017 that made me think. Ghanaian George Mwinnya wrote about his confusion upon learning that the United States had an independence day - he had only known of formerly colonized countries like his native Ghana having independence days. You can read the whole thing here, but I wondered a little at the realization. Yes, we were technically a British colony, but it wasn’t our Indigenous populations rising up against colonialism. It was the colonists themselves.

Which then makes me wonder if that’s why Americans call it “Fourth of July,” and not “Independence Day” - to distract us from our colonial past? Our “revolutionary” uprising? (I put “revolutionary” in quotation marks because much of the American Revolution was about maintaining the status quo.)

For centuries, BIPOC people have had mixed or hostile feelings toward celebrating the country that stole their land or labor and oppressed them through cultural and literal genocide. As a White American, I always had the luxury of focusing on words, instead of actions. I celebrated the Bill of Rights, and the idea of democracy, the audacity of the American Experiment. But I’m feeling less like celebrating than ever this year. In part because the actions are harder to ignore.

Between climate change, the threat (albeit relatively low) of global nuclear war, burgeoning theocracy, and a Supreme Court that has relegated me and millions of other uterus-owners to second-class citizenship, it’s tough to find anything to celebrate. It’s easy to feel beaten-down, freaking exhausted, and hopeless. But looking to the past, I take some heart from the fighters who went before us, even as I don’t have any real solutions to the problems we face.

I also got thinking about independence, and what it truly means. The United States has long prided itself on independence, freedom, and individuality. Those are related, but separate ideas. For White America, particularly in the 1950s, the concept of pioneers has been deeply steeped into our culture, especially in the Upper Midwest, where I grew up. Pioneers were self-sufficient farmers who braved the wilderness to carve out civilization with grit and intelligence. Or, so we’ve been taught. Dr. Sarah Taber has another explanation (seriously read it). And despite growing up with a deep-seated love of Laura Ingalls Wilder, rereading the books as an adult makes you realize, even in the highly romanticized version of Wilder’s real life (one that cut out other people, abuse, etc.), how utterly dependent the Ingalls were on railroads and store-bought goods like cornmeal, salt pork, and seed.

“The Long Winter” illustrates this the best, and makes me wonder how the people in the town would have fared if they had shared resources. Rereads also made me realize how, despite their eternal quest to replicate the prosperous farms they left in New York and Wisconsin, Pa was never able to make any of their farms “pay,” instead cobbling together jobs with the railroad, in construction, and in real life, as postmaster. And how, despite Laura serving as his “half pint” who was “strong as a pony,” the entire family was utterly dependent on Pa’s physical labor and health.

There’s a lot of self-sufficiency rhetoric winding around the internet these days, most of it around homesteading, home gardening, and food preservation. And while some of it is more self-aware (particularly the food sovereignty movement), most of it replicates the pioneer mentality that totally ignores the history behind settler colonialism. The more I study the food systems of the past, the more I realize how global they really were.

Think about it - by the mid-19th century, when European immigrants and White Americans were colonizing the last pieces of the continent (and killing and displacing tens of thousands of Indigenous people), almost all of them were totally dependent on canals, railroads, and national and global markets, to receive goods for household use and to ship their crops to market. Even earlier in the century, folks traveling on the Oregon Trail (remember the game?) were reliant on salt pork processed in Cincinnati (a.k.a. “Porkopolis”), store-bought cornmeal, agricultural seed ordered from catalogs, commercially milled fabrics, imported sugar, coffee, spices, and mass-produced agricultural and kitchen equipment, fabric and leather. The myth of the early American colonist being totally self-sufficient, raising flax and wool to make their own fabrics, cutting lumber and building their own buildings, producing all their own food, etc., was just that - largely a myth (although not for Pre-Contact Indigenous people). By the 18th century, most early American households owned at least one other person who they forced on pain of violence or death to do the hardest and heaviest household and agricultural labor. They largely did not pay for the land they occupied. Child labor filled in the gaps. And while plenty were unlucky enough to be tenant farmers to wealthy land-holders who claimed to own hundreds of thousands of acres (awarded by “divine right,” of course), they still had access to a global network supplying them with raw and finished materials like sugar, coffee, tea, olive oil, spices, dried fruits, chocolate, nuts, etc. Many of which were produced by slave labor.

Our modern concept of “independence” often stems from this mythology around self-sufficiency. Freedom from tyranny is worth fighting for. The freedom to make your own choices is another that Black and Indigenous people have been trying to reclaim for decades. The freedom to own land and produce your own food in the context of centuries of being owned and later forced into sharecropping (and even later, denied aid and loans by the USDA and losing land at ten times the rate of White farmers). The freedom to reclaim cultural foods and practices once made illegal by those who stole not only the land you came from, but also your children. And these days, for women, the freedom to vote, have access to capital, and decide how, when, and whether to have children are incredibly recent in the grand scheme of America, and that last one has just been reneged on and denied to millions of Americans.

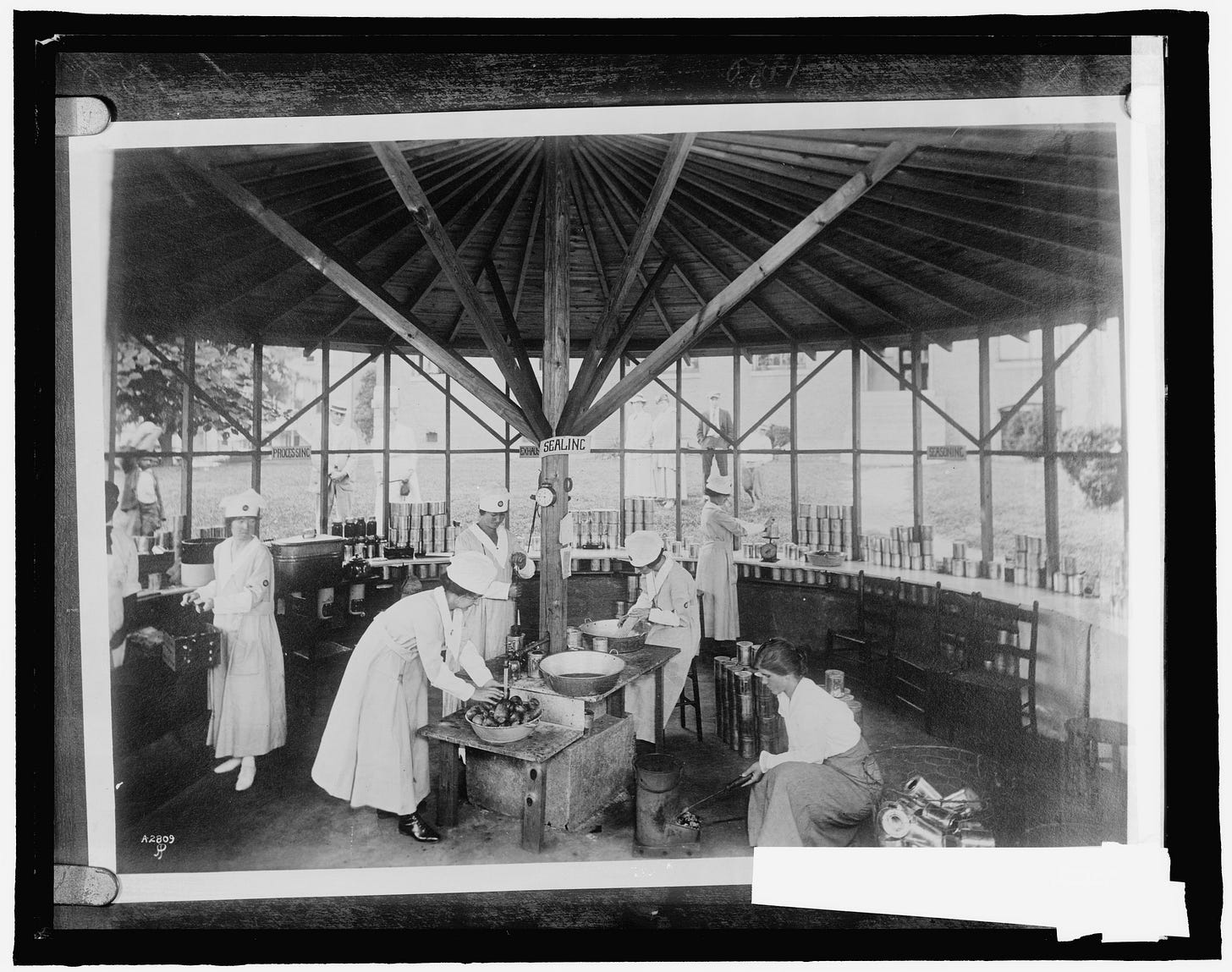

“Feed yourself and free yourself” is a concept that has existed for a long time, especially in BIPOC communities, as Leah Penniman has argued. And in many ways, she’s right. In an era of increasingly destabilized global supply chains, having a pantry full of food helps you not be beholden to anyone. But how free are we really? Canning jars and lids still have to be bought from stores - even the most accomplished glassblower would have a hard time making cans able to stand up to pressure canning, and none of us are glassblowing jars. We buy salt, vinegar, and sugar for preserving from the store, too, and have for the last 200+ years. We pipe in gas or electricity to power our stoves and dehydrators, and buy mass-produced kitchen utensils. The vast majority of people are not raising grain for home consumption, and yet lots of homesteaders are making bread.

The point is, no person is and island, and the decisions we make often have community or even global repercussions. Self-sufficiency is admirable, but is always tied to things we don’t often have control over - physical health and ability, access to land and other resources, knowledge, and yes, money to purchase the things needed to be “self-sufficient.” I think instead we might be better off building relationships. Why should I try to grow dozens of types of fruits and vegetables and can pickles and peaches and tomatoes and applesauce and make jam all by my lonesome, when I could share the labor and swap surplus?

Historically, people shared labor to produce food. From hunter-gatherer times to early agriculture, people worked together to share labor, knowledge, and resources. Husking bees, community canneries, and maple sugaring are all examples of historical peoples coming together to share labor and resources as recently as the 1940s. And while utopia is always elusive, no matter the time period, I can’t help thinking that our time and energy would be better spent on cooperation than trying to always go it alone.

The same thing goes for politics.

I’ve been working on several pieces on the future of food (spoiler alert: I’m going to be talking a lot about the past), and I’ll definitely be talking about our globalized food system (with a guest post or two!). But the more I think about the future, the more I worry that time is running out, that even though many of the solutions to our current problems lie in the past, we’ll consider using them to be a step backward. But I also take heart from what people in the past have already accomplished, what we can learn from them, and how we might move forward.

This year I’m not going to celebrate Independence Day as I once might have (at this point in my life I’m also a curmudgeon with a sensitive dog and both of us hate loud noises, so fireworks can just go you know what). I’ll be joining a lot of folks who came to these realizations long before me. I don’t know what your plans are, dear reader, but since you made it through the end of this ramble, I hope it made you think as much as I have. There are a lot of terrible things in the world, but there are a lot of good things, too. Here’s to a freer, more cooperative future.