Food Prices & Politics

A brief history of price gouging, inflation, price control, and corporate consolidation

Hello dear readers! I finally have an extra few days off where I don’t have to spend them doing the 8 million tasks that usually take up my “free” time these days, so I thought I’d catch up on some writing with a lot of things that have been percolating in my head for months now.

It’s also the day before the US presidential election, and I wanted to address something I think the media is not covering well: grocery prices.

Top Democrat and presidential candidate Vice President Kamala Harris has promised to go after price gouging on groceries. The media has largely scoffed. But laws about price gouging and struggles with high food prices during global emergencies are nothing new. Most states in the US (but not all) have price gouging laws on the books. There is no federal law on price gouging, although there is at least one bill currently in Congress.

But what is price gouging? Price gouging is when a purveyor artificially and excessively inflates prices in times of emergency or economic disruption, generally on essential goods. Unscrupulous people can take advantage of disruptions and need to make enormous profits. Think people who bought up pallets of hand sanitizer to resell at a huge profit early in the pandemic.

There are, however, federal laws against price fixing, which is when two or more companies collude to fix prices at a certain level, usually to corner the market and artificially increase profits. This is a violation of anti-trust legislation and can lead to investigation and criminal prosecution.

Most media outlets have blamed price increases on inflation, which has a variety of factors, not limited to increased demand for limited supply, supply chain cost increases, increased wages leading to increased prices, etc. But that is not the whole answer.

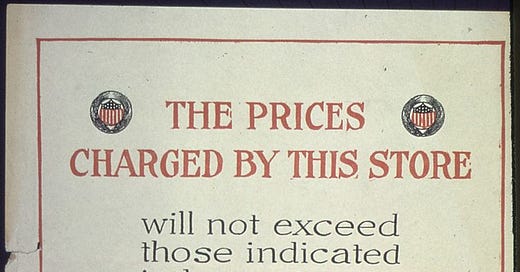

Price gouging and inflation are nothing new. Food prices skyrocketed during the Civil War, especially in the South. Food prices also rose significantly during the first decades of the 20th century, thanks to industrial depressions and World War I. The “high cost of living” bedeviled millions of Americans. During the First World War, the U.S. Food Administration was eventually given wartime powers to regulate the entire food chain, although Food Administrator Herbert Hoover was careful to avoid both mandatory rationing and over price controls. Instead, the United States became the largest purchaser on the market, and set prices that way. Newspapers also published price lists of what regulators considered fair market prices for a variety of essential goods. Consumers were warned that anyone pricing in excess of published prices was price gouging.

During the war, entire industries, including the meat packing and dairy industries, were investigated by Congress for price gouging and price fixing. Business leaders were called before Federal boards of inquiry and to testify in Congress, opening their books to inspection and explaining everything from staff salaries to production costs. In both instances, little evidence was found, although there were real concerns about corporate consolidation of meat packing. Post-war, dairy cooperatives were again taken to task, this time prosecuted under anti-trust legislation for cooperatives and accused of price fixing and collusion. The lack of evidence resulted in a new law exempting agricultural cooperatives from being prosecuted under anti-trust legislation.

During the Second World War, the US Office of Price Administration oversaw rationing and set price controls on everything from foodstuffs to rent. It was immensely popular with everyone except business leaders, who first weakened it and then forced it to shut down shortly after the war.

Does any of this sound familiar? Today, we also have anti-trust issues with food production and retail – a problem that long predates the COVID-19 pandemic. I’ve often said that the food history trend of the 20th century is corporate consolidation. And indeed, the variety of choice on our supermarket shelves seems to belie that, including some very old food company names. But while the number of food companies in the late 19th century exploded, by the mid-20th century, so many of them had been bought up by competitors that they had been consolidated from hundreds of local and regional brands into just a few national brands. Today, that number is even smaller. Just a few corporations – Mondelez International, Unilever, Kraft-Heinz, and the world’s biggest – Nestle – own the majority of food brands across the world. A single company can even own brands that seem to be in competition with each other – but the profits all go to the same company. In the U.S., meatpacking is dominated by just four companies – Tyson, JBS, Cargill, and National Beef - who control 85% of the market. McDonald’s just sued all four of them for price fixing.

There certainly have been extenuating circumstances in the last five years – supply chain disruptions were real, demand shifted enormously as restaurants and theatres were closed, and peoples’ purchasing habits changed. But the majority of the media coverage doesn’t seem to want to admit that real price gouging took place. For instance, in September, 2024, NPR took a deep dive into companies’ accounts and showed around 1% increasing in profits. But nowhere in the article did they address the issue of stock buybacks.

According to the Harvard Business Review, stock buybacks are when companies take profits (or sometimes go into debt) to purchase their own stock on the open market. Why? Generally, best practices with profit are to raise wages to reward productivity, invest research & development, and/or expand the company. Instead, stock buybacks reward senior executives with increased stock prices (since stock is often part of their compensation packages), and reward shareholders with increased dividends. Stock buybacks took a brief hit in 2020, but have exceeded pre-pandemic levels nearly every year since.

Companies also haven’t been trying to hide their new economic strategy. According to Forbes in February, 2024, companies are flat out admitting that as demand declines, their plan it to simply raise prices as high as they can to make up the difference.

Food production has always had limits. After all, unless the population increases, food consumption levels are going to stay relatively flat. But creative companies found ways to make money. First, companies profited by adding value through processing (i.e. canned goods, candy and soda, breakfast cereals, pickles). Then, companies took advantage of government policies and technology to lower their costs (i.e. price floors on commodity crops that allow companies to buy crops for less than they cost to produce, and then transform them into ultra-processed foods). Then, companies increased sales by increasing demand for food items like fast food, snacks, soda, and other ultra-processed foods by making them deliciously addictive. But people can only consume so many foods, and health-conscious consumers are starting to turn away from ultra-processed foods like chips, candy, soda, and cereal.

Companies got used to very high profit margins and are increasing prices to maintain those margins. However, ultra-processed foods were previously among the less expensive, so the poorest Americans are the hardest-hit by price increases.

There are other disruptions at play besides corporate greed. The war in Ukraine made international agricultural additives prices skyrocket. Climate change is hitting a variety of crops hard. Wildfires, hurricanes, drought, excessive heat, excessive rain, early or late frosts, and flooding are all negatively impacting crops around the world, including blueberries, oats, olives (and therefore olive oil), chocolate, and tree fruits like cherries, oranges, almonds, and more. Even though our globalized food supply should in theory help us weather these… well, weather events, the consolidation of production into monocropping in concentrated areas has meant that one hurricane or flood can wipe out the majority of a crop. And when multiple natural disasters across the world hit? An entire food chain can be disrupted.

At the heart of all of this disruption, however, is still corporate greed. Even when supply changes and wages increase, no corporation is willing to reduce profits by even a little bit. So instead of taking a hit, they pass on every price increase on to the consumer. And instead of rewarding employees with higher wages for increased productivity, they use the profits to buy back their own stock to artificially increase the price (by creating demand where there otherwise is none) and inflate their compensation packages and keep their shareholders happy.

The quieter story is that the 2017 Trump Administration corporate tax cuts weren’t invested in wages or research & development or decreasing consumer prices either – they were almost exclusively used in stock buybacks.

So while food prices are incredibly complicated, and there are lots of factors at play - corporate greed is still a major concern. And when it comes to essential goods like food, that’s just wrong. The past 10 years have seen increased wealth transfer from the working and middle classes to the highest echelons of wealthy – through tax breaks, stock buybacks, market consolidation, and yes even price fixing and price gouging.

I don’t think any one person – or the government – can fully control the markets. Nor do I think they should. But consumers need protection from predatory business practices. And I know which party is going to support more consumer protections and which party wants to remove all the guardrails for corporations and the ultra-wealthy (and, according to experts, tank the economy) at the expense of working people. Do you?

Tomorrow I’m voting for a saner, more stable future where ordinary Americans’ needs are put above record corporate profits. I hope you’ll vote, too.

Want more food history, historical recipes, book reviews, and more? Visit my website: TheFoodHistorian.com.